|

Frances Noble talks |  |

|

|

Life |

|

|

How did you come to Norwich? |

|

|

Where did you study art? I went to Reigate School of Art in Surrey and had a really good time, although it was a difficult personal time. The Principal, Mr Poulter was a gem – he had been there since the war and both loved, and was loved by the students. He was a big, fat, chain-smoker. When the Vice-Principal took over he had a much more commercial attitude to things and the atmosphere changed. I studied Applied Fine Art. I wanted to do sculpture but I didn’t like the department – it was intimidating and hippy. I spent a lot of my time studying architectural decoration with old-master type tutors in what was a very small department. It was exactly right for me at that time. One of the tutors was interested in anatomy and so I learnt about figures then and decided that I had to be a sculptor. I always knew I would make a career in art and I was optimistic that I would be able to earn my living at it. How did your first commissions come about? At the end of the course one of the graphics tutors gave me some addresses to follow up and I eventually made contact with James Gardiner in Havistock Hill. He told me that if I could make figures I could probably earn a living. I made two sample figures which he liked and I was then commissioned to make figures for a diorama made by Philip Kemp for the Commonwealth Institute. I also did some model making and restoration work. There is a fantastic Royal Barge at the Maritime Museum in London and it was in need of restoration and re-gilding. The barge itself had been made by William Kent for Prince Frederick. A friend and I took that on under the auspices of a man called Kim Allen and it was a great success so more work began to come in. I helped to restore a scale model of London’s Roman Catholic Cathedral and I made a life-size figure for the Gold of Eldorado exhibition. That figure was very striking. Dressed in fantastic gold ornaments, it stood at the entrance to the galleries and was very evocative of the richness and strangeness of what visitors would see inside. Foolishly I didn’t take any photographs and the only picture I have is a rather faded newspaper cutting of Princess Anne opening the exhibition and standing next to my figure. You make miniature figures and life-size models – how different is it to work at such different scales? I designed a chess set based on Tudor court characters recently which was a great contrast to the life-size figures I do for museums and exhibitions. The idea started out as a series of busts of the characters, but evolved into miniatures. I used Milliput to model the pieces, it’s a wonderful material – very malleable and easy to work and it hardens off amazingly quickly with a little heat from the oven in the kitchen! I use a craftsman’s Dremel drill and rasps to complete the complex modelling of Tudor ruffs and so on. The king was based on a bust of Henry VIII and the queen was Elizabeth I of course. The most difficult figure was Cardinal Wolsey – I had only a profile portrait to go on and had to invent how he would have looked. I’m pleased with the result. I made the pawns as Tudor roses and the castles are complex Tudor chimney stacks. After making the originals I had to construct silicone rubber moulds to cast the resin figures. Unfortunately I haven’t yet found anyone who would like to produce the set commercially – but it could happen – I might do it myself! I like the contrast between working on life-size figures and the physical movement involved in that and the intensity of concentration that goes into making miniatures. |

|

|

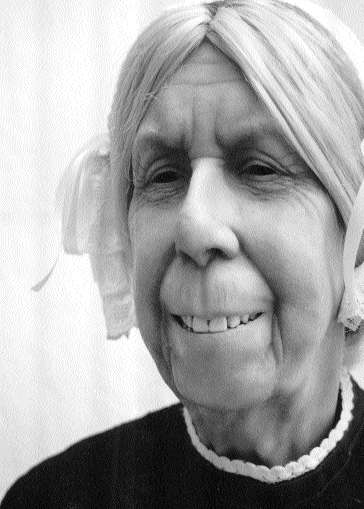

They look wonderful and amazingly realistic for such small figures, but they don’t have the drama and seeming life of this old woman do they? I am really pleased with her – the head was modelled on an elderly lady who is a friend of mine. I asked if I could do her portrait and she gave me three sittings, where I was able to take lots of photographs and measurements. I made the head and then had to devise a character to go with it. At first I thought it should be Juliet’s nurse (from Romeo and Juliet), but then I began to wonder what life expectancy was in Verona at that period and how old, or young, Juliet’s nurse would have been. I had no idea of course, so I decided to make her into a Quaker lady instead. I didn’t think it was appropriate to ask my friend if I could do a body cast, which is the best way to do it, so I carved the body in polystyrene and clad it in a fibre-glass shell to give it rigidity. I made casts of another friend’s hands and completed the costume to suit the character and the period. She has become a show figure – I take her around with me to show people what I can do. I’ve even given her a name – Sampada – that’s my friend’s Buddhist name and I feel it really suits the peacefulness of the figure. |

|

|

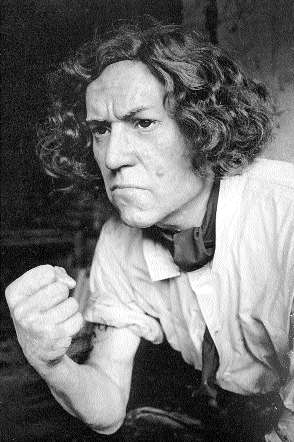

You must have to do a lot of research to realise your work. That’s very true and I enjoy the research involved in creating historically accurate as well as visually accurate figures. It’s often the research which connects me most with the people who commission things from me. They give me references and point me towards the things I need. We are so lucky in Norwich to have the wonderful Costume Museum at Carrow House. It’s the perfect source for my work. I can see how you might carry the chess set around to show people, but how on earth do you transport the life-size figures? Carrying the figures around is always a problem. I have a Volkswagen Golf because with the back seat down I can take a figure in the back. Sometimes I do put seated figures in the passenger seat. I always get funny looks from other drivers when I’m driving figures around, you can imagine how it looks with Sampada lying in the back! You have been commissioned to make figures by one of the major potteries, what have you done for them? I have done a whole series of pieces for Royal Doulton. Some of them have been very successful but some weren’t taken up in the end. I’ve enjoyed working on all the proposals with them though. I did a series of philosophers’ heads – Aristotle, Plato and Socrates. I needed to be faithful to their known likenesses, so I did the research for those at the V and A. It was a good experience (especially as my son has been studying philosophy) and widened my horizons as I read quite a lot about them and their ideas. The busts are about 17 inches high, including the base, and are monochrome, which is an unusual format for a pottery. They were delighted with them. I also did a commemorative bust of the Queen Mother for her 100th birthday. I’m not so pleased with that, though they were. They asked me to flatter her – her face could have been a little wider. Then I was commissioned to do a bust of Diana for what would have been her 40th birthday, but everything had to be approved by the Memorial Committee and they didn’t give permission for it to be produced. That’s a shame because the prestige of sculpting that piece would have done me a lot of good professionally. What makes a figure successful do you think, and what makes you satisfied with the finished work? What I really want is to portray a character that lives, to be able to put my heart and soul into it. There’s the real challenge, to make the character convincing as if they were someone I knew well, not just the product of research for a commission. The figures which were made for the Tollhouse Museum in Great Yarmouth show what I mean. They wanted some figures for the small dungeon cells – to make it more interesting for the public. I was lucky, there was a lot of information about two particular prisoners, their height, background, character and physical appearance. Charles Girdlestone, for example, had had smallpox, had a boil on his face, was slow to anger, finally exploding in rage. Sarah Hunnibal was a local prostitute – very fiery and feisty. The models I used for the bodies were really involved in developing the characters, like actors getting into their parts. You can see how the model for Girdlestone expressed the pent up anger of the man – just look at the way he held his hands and arms and the brooding angle of his head and shoulders. |

|

|

Is it enough just to be ‘true-to-life’? I’ve said a lot about accuracy, but in reality it’s the distortions in the figures which really give the appearance of reality – of life. I would really like to be able to do some commissioned portrait heads. To say something about the sitters beyond what the physical form allows. But I’m limited because I need to earn my living. Whenever I haven’t any work I begin to worry. I wish I could do bigger and better projects, but it’s like spinning plates on poles – you have to keep things moving or it all goes horribly wrong. What would really change your life and help you move your work forward? What I would really love is the same as lots of artists and makers would ask for, that is someone to organise me, drive me and market my work so that I can concentrate on the work itself. But I have to say that having to manage without that has made me stronger and developed sides of me that I never had before. Where did your influence and inspiration come from? What deeply sparks me off is the art which came out of Paris at the turn of the century, Picasso, Braque all the post-impressionists. I’ve never felt strongly about the impressionists. But really all art, throughout the ages, is an inspiration. For me the definition of art is that I should look at a work and be transformed to a higher state of being – so all sorts of artists are interesting to me. I love the physicality of art which can wake up forces within us that we never knew were there. That’s why, when we go to an exhibition, we can be awakened by what we see, looking at art can inspire us to develop personally. Which are your favourite museums and galleries? I love the British Museum and Tate Modern they are my favourite haunts, but I don’t go nearly often enough. I don’t need to see a lot to feel satisfied, just to look at a few things, I don’t need everything, I know when I have seen enough for one visit. I spent a wonderful week with my son in Paris when he was young showing him things that I had first seen when I was much younger. When he was 15 or 16 we went to Greece to the Parthenon – even though I had been there before, seeing it all again through his eyes was a very moving experience. His excitement was my reward. |

| Home Page | Find out more about Do Phillip's work |